Find the podcast feed and the most recent episode below.

Sign up to the newsletter to get new podcast episodes in your inbox.

Training Load Monitoring & Planning: Using ACWR with Siobhan Milner MSc, CSCS – Total Performance with Siobhan Milner

In this episode, Siobhan Milner (Strength & Conditioning Coach with the Dutch Olympic Team) takes you through an introduction to training load monitoring and planning, and how to use the acute to chronic training workload ratio model (ACWR) specifially. This episode is perfect for coaches and athletes who may have limited access to a strength and conditioning coach in their own setting, and want to know how to monitor and plan their training load.

Thoughts about this episode? Let me know over on IG!

About Siobhan Milner:

Siobhan Milner believes we’re made to move. She is an exercise scientist with over a decade of experience working with everyone from Olympians, to premier-league hockey players, to patients with low back pain, to professional dancers, to individuals with cancer and chronic lung diseases. She uses her expertise to help you improve your athletic performance, and prevent, manage, and recover from injuries.

Siobhan is currently a Strength & Conditioning Coach with TeamNL (Dutch Olympic team), training Shorttrack Speed Skaters, the national Curling team, and talent and elite beach volleyballers.

She also works with several independent athletes, primarily in endurance sports and dance, and with clients seeking her knowledge in injury rehabiliation.

Siobhan Milner is a believer in evidence-based exercise prescription, but also strongly believes that all training should be athlete-focused; specific to their goals, their needs, and their likes and dislikes. Most of all, she loves seeing change in her athletes’ lives – whether it’s at the level of function, pain, or performance.

Are you ready to improve your sporting performance, or change the way your body feels? Get in contact with Siobhan Milner here to discuss how she can help you get the most out of your body.

Featured on the show:

Where to find Siobhan:

Website: www.siobhan-milner.com

Instagram: @siobhan.milner

Facebook: Siobhan Milner Athletic Performance & Rehabilitation

Twitter: @siobhancmilner

Tiktok: @siobhan.milner

Important Links:

- Stay up to date on the Total Performance podcast where you can join Siobhan Milner and guests as we explore the many aspects that come together to build our total performance.

- Find Siobhan Milner on Instagram, Twitter, & Facebook

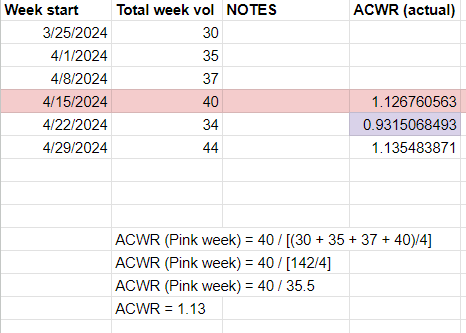

- See the example calculation Siobhan talks about in the podcast episode below. You’ll also see an example deload week (in purple), and another building week following.

Automated Transcript: Training Load Monitoring & Planning: Using ACWR with Siobhan Milner, MSc, CSCS

Siobhan Milner: [00:00:00] Hi everyone, I’m Siobhan Milner and this is Total Performance, a podcast dedicated to all things athletic performance and injury prevention. Join me and my guests as we explore the many aspects that come together to build our total performance picture. Let’s get into it.

Hey everyone, today I’m going to be talking about load monitoring. So I’m going to be talking about what training load is, and I’m going to give some ideas on how to plan and progress it, and how to monitor it. We talk about training load and how to manage it a lot, but I think a lot of people don’t actually know what training load is, so I’m going to try explain that first as well.

So very simply, training load is the total amount of training that you’re doing in a week, but often when we’re looking at training load, we’re not just looking at duration, we’re not just looking at the amount, but we’re also looking at the intensity. So we often use some measurements where we come up with something called arbitrary units.

And an arbitrary unit is pretty much a way to measure something without using any specific standard or measuring system. So, you know, when we measure distances, we might measure things in meters, but when you’re trying to compare, for example, A running session versus a team sport session versus a weight training session.

You know you could measure the duration of all of those sessions when you don’t have the intensity that doesn’t really tell you that much about them compared to each other. So we come up with these arbitrary units and we usually just see them in a number format. To be able to compare all of these types of training.

So one of the ways we’ll do that is we will look at the duration of the session in minutes. So let’s say 60 minutes and we’ll use RPE. So I think some people are familiar with RPE. It stands for Rating of Perceived Exertion, and it’s a way to measure how hard you feel like you’re working during training.

So, it’s really just a 1 to 10 scale sometimes we also use the Borg scale, which is a scale from 16 to 20. So there’s different kinds, but often when we’re doing the calculation that I’m going to talk about, we often use a 1 to 10. I, for myself, will just use a 1 to 5 scale, but when I’m working with athletes, I tend to use a 1 to 10 scale because I think it gives me a slightly nicer picture, but it kind of depends on how, accurate you need to be with that RPE, that difficulty rating.

Because, of course, if I compared, for example, 60 minutes cycling to 60 minutes running, it’s likely that the running is going to be harder, so it’s going to have a higher RPE. So, if we said, I’m just going to make this super simple, if we said the running was an RPE of 10, it would be 60 times 10, so you would get 600 arbitrary units.

That’s the number that we use to kind of rate the training load of that one session. And let’s say you did 60 minutes of cycling and it was only an RPE of 5, so 60 times 5 is 300. So you would have 300 arbitrary units for that session. So even though they were both 60 minutes we see that the running has the higher training load because in our example it’s 600 and the cycling has a lower total of 300.

Now I know for some people the second they start hearing numbers or calculations, their eyes glaze over, and their ears switch off. I’m someone that I actually quite like math if I take the time to, to get my head around it, but I do need to see it visually. So what I’m going to do as well is I’m going to make a few kind of, graphics and I’ll put them on the show notes page.

So you can see examples of how I have worked through. the calculations that I’m about to talk about. And I promise it’s actually very, very, very simple. I was mentoring a young strength and conditioning coach recently, and he was, telling me that he found the statistics and the calculations quite scary, and I was like, don’t worry, this is one of the most simple ways to measure ever.

And even if you’re not going to do this for yourself, if you’re an athlete or you’re a coach, you are probably going to be presented with some of this training load data by strength and conditioning coaches or by sports scientists. So this just might help you have a little bit more of an understanding of it, even if you’re not going to do it for yourself.

But if you are, Training by yourself and managing all of your training load by yourself. I do think this can be helpful to do once in a while So I’m gonna get to that But maybe my first thing that I’m gonna say is if you are someone that is training totally by yourself And you don’t have a coach, you can do pretty well I think by aiming to just add around 10 percent total volume or total load Each week.

You don’t want to do that infinitely forever, because of course, the absolute amount changes as well, the more You increase per week,

and it is probably a good idea to think about having some deload weeks if you’re very consistent with your training. If you’re an amateur athlete, sometimes you’re going to have deloads happening automatically just with life, like if you have a family, if you have a job, if you travel, if you have kids, you might have weeks that you do pull back training anyway, because of things outside of your control, so then you might not need that planned deload week.

I, for myself, because I will travel a bit still with work, I don’t plan that many deload weeks per year, but I also have been tracking my training for Oh my gosh, okay. This is crazy. I actually just had to look it up. I’ve been tracking my training for 17 years now. So I will say, I’ve been tracking my training for 17 years.

So I have a pretty good idea of how my body responds to things and I have a pretty good idea of how hard to push and when I need to go. Okay, now it’s time for a deload or it’s time for a deload sooner than planned. But I think it takes time to learn how your body responds. And of course as we get older, That changes too.

So you’ve got to, you’ve got to be aware of that and just know that when your life situation change and stress changes , your training will be affected by that too, even if it’s not a physical change.

But now I’m going to get into how you can actually do some calculations to monitor your training load. And also hopefully progress it so you can use your training tracking to keep an eye on things Why is this important? This is maybe one other important thing to tell you before I talk about this as well There are so many people who come to me with injuries primarily because they’ve had massive peaks or drops in their load.

So what I mean by that is they’ve done way too much too soon or they’ve done way too little for too long and then tried to do way too much again. So our bodies are really, really good at adapting to load. They’re really, really good at adapting to stress, but we need the right amount of stress to adapt.

We don’t want to totally overload the system because that’s when we’re more susceptible to injury and illness.

So I’ve seen this sometimes as well with amateur athletes on Instagram who I’ve seen them sharing things about races that they’re planning to take part in and then they totally ramp up in a really short amount of time and then they might not even get injured right before the race but they get sick or something or something goes really wrong and then they get to the race and they fall apart.

Or they fall apart right after the race. So if we can actually plan in advance and progress slowly, that’s way less likely to happen. And just remember, it does take time for structures in your body to adapt to training as well. So things like muscles, you might start to see that they adapt in the first couple of weeks.

You’ll also see these neuromuscular changes, so Sometimes when you feel stronger already after a week, that’s not so much that something has changed at the muscle level, it’s more that the, the nervous system, the brain, has gotten better at firing the signal to get those muscles to activate and work at the intensity that you want them to.

Tendons will adapt a little bit slower than muscle as well, so this is why with some things like running you’ve got to progress a little bit slower than say, you feel like you can for actually your lungs.

Because especially some cardiovascular adaptations can happen really really fast. There’s some transient ones that happen within days as well. And then things like bones, they take more like several months to adapt as well.

So just remembering that all of these different fitness adaptations happen on different timescales to each other, and that means that in general, we want to take our time to build up our training load, rather than going from 0 to 300 in two weeks. Okay, now I’m going to talk about Acute Chronic Workload Ratio.

So, one of the ways that we can monitor our training load is by using something called the Acute Chronic Workload Ratio. Like many models, it’s not perfect, but I find it’s a pretty good estimation, and like I say, it’s very easy to use. So bear with me, because I will talk about some math, but I promise it’s actually super simple, and I will put some Graphics and things up on my Instagram page and on the show notes page for this episode so that you can see it and get a bit of an idea of how it works.

You can actually often even find calculators online for the acute to chronic training workload ratio. It’s the ACWR. So one of the main things that we’re often doing is comparing our mileage for things like running, swimming, cycling or the duration. So again in minutes from the last training week compared to our average for the last four to six weeks.

I tend to look at it for the last four weeks. Some models look at it over six weeks.

So I’m going to give an example just for running and I’m just going to give an example with mileage in the beginning and then I will talk about these arbitrary units that I talked about earlier as well. Okay, so let’s say I’m running 40 kilometers a week. What I would need to be able to do this acute to chronic ratio is I would need four weeks of my training to look at, to compare.

So let’s say that I had four weeks. That were building up towards 40 kilometers. So again, I’m going to put a picture of this on the show notes page so you can have a little look as well, just in case you need to see it visually, but I will try to keep it quite simple. So let’s say week 1, I ran 30 kilometers total.

Week 2, I ran 35. Week 3, I ran 37. And then week 4, I got up to this 40. So if I wanted to work out the acute chronic workload ratio for this week, the week of 40 kilometers, What I would need to do is I would need to take this number, the 40, but then I would need to get the average total volume for the last four weeks.

Now again, I promise this is super simple. So I would just take all of those total volumes for the last four weeks, I would add them together and I would divide them by four, that would give me the average. So I would go 30, Plus 35, plus 37, plus 40, divided by 4. So to get the average, I’ve added those last 4 weeks together and I get 142.

But to get the average, I’ve then got to divide that by the number of weeks, which is 4. So 142 divided by 4 gives me 35. 5. I promise we’re almost done. And like I say, when you see it, it’s actually really simple. So then, if I want the acute chronic workload ratio for this week that I’m talking about, this 40 kilometre week, I would go 40 divided by the average volume for the last four weeks, which is 35.

5 kilometers, and that would give me an acute chronic workload ratio of 1. 13. So, I’ll explain the significance of this as well.

There’s quite a few different papers looking at acute chronic workload ratio, and when we get this number at the end, It tells us a little bit about our injury risk. So, there’s a sweet spot, and this sweet spot kinda depends on the paper you’re reading, but usually, that sweet spot sits somewhere between 0.

8 to 1. 2 or 1. 3. This is the optimal workload amount, and it’s the lowest relative injury risk. It doesn’t mean injuries won’t happen. Hopefully by now you realize that injuries are very multifactorial and we cannot prevent them all, but If you get a number at the end and it’s somewhere between that 0. 8 to 1.

2, 1. 3, you’re usually in a pretty good spot. If the number that comes out when you’ve done this calculation is less than 0. 8, this is actually also the danger zone, because under training can also lead to injury risk, and especially we don’t want to drop our training amounts too much in, for example, our deload weeks, if we want to avoid injury.

Because when we get back to training, then we would see a really big peak in that number, and then we’re in an increased injury risk. So we said less than 0. 8 is an increased injury risk. 0. 8 to 1. 2, 1. 3 is usually about the sweet spot. But then we have other numbers that could come out of course. So if the number that came out was somewhere between 1.

3 to 1. 5, again, depends on which papers you’re reading, then we would say you’re at a workload that is at a increased injury risk. If the number that comes out is more than 1. 5, this is kind of the danger zone. This is where it’s the highest relative injury risk. So especially there, that’s a really, really big increase in, Total workload compared to what you’ve been doing for the last four weeks.

And again, you can compare this to six weeks if you prefer. So if you’ve got a number coming out that high, that’s where you’ve definitely increased too much too soon. So just going back to this example, where there’s been the total running volume of 30 kilometers, 35, 37, and then 40. And we did this little calculation and the number we came out with was 1.

13. Then we know we’re in that sweet spot zone, we’re between that 0. 8 to 1. 2, 1. 3.

And this is why I also often say it is quite simple to just think of adding about 10 percent per week, because if you’re doing that, you’re usually going to end up with an acute chronic workload ratio of about 1. 1 anyway, so then you’re within that sweet spot, that good zone, where we’re in the lowest relative injury risk.

But, of course, Now we’ve only taken into account duration, right? And remember at the beginning I was talking about say how a run is usually harder to recover from because it’s a higher RPE or so things like impact compared to something like a bike ride which is usually easier we don’t have the same impact.

So when we’re doing these sorts of calculations we can’t really take into account this different of like on feet versus off feet modalities, but what we can take into account is how hard they feel, the intensity, which is going to give us a slightly better approximation as well. So, what you can do then, Is you could take a session, like I said earlier, and you take the number of minutes and the RPE and you just times them by each other.

So if it was an RPE of 6 and it was 100 minutes, 6 times 100 is 600, so that would be your arbitrary units. So then what you would need to do is you would need to go through and do that for every single activity of the week and end up with arbitrary units. And that’s the way you can compare those activities to each other.

But then you would do the exact same calculation that I’ve just talked about for that running distance. So you’d get the total arbitrary units for all your training sessions for week one, two, three, four, four being that week that we’re looking at in particular. And then we would take the arbitrary units, the total for week four.

And divide it by the average total for the last four weeks to get our result. And then those numbers still mean the same thing. So we still don’t want less than 0. 8. We don’t really want more than 1. 3, but we especially don’t want more than 1. 5. There’s a few different kinds of acute chronic workload ratio models.

But this is just like a really simple introduction to it. I don’t think you need to make this super complicated, especially in the beginning. What you need to track to be able to do this is you need to track your RPE, so how difficult your sessions feel. Like I say, I just do mine on a scale of 1 to 5, but with athletes I would recommend more like the 1 to 10.

And you need to track the duration and of course you’ve just got to be keeping a really good record of what it is that you’re actually doing in training. I know a lot of people use things like Polar because their heart rate monitor tracks on it, their Fitbits, Strava, Training Peaks, things like that. I’ve always used a really old school orienteering website called attackpoint.

org, it’s totally free. I find it really good for, Putting in all the measures I need and then I also leave notes on everything. I think this is super important as well just in general when you’re tracking to leave notes to see how you’re feeling because of course we can look at all this data but the other big thing is if you look back and you’re seeing notes like so tired I’m sore over and over then that also should give you an indicator of when things are a bit too much too soon.

So that’s just a little bit of an introduction to workload and how to monitor it. And like I say, with planning it, you can kind of work backwards as well. So you could work backwards and see, okay, where do I need to be? Let’s say you’re trying to run a particular distance race. You could see where do I need to be six months from now, four months from now, wherever it is, and then work back to calculate your acute chronic workload ratios.

And, you know, you can plan in your recovery weeks that way as well. So usually for me, when I’m planning a deload week, I try to get the number at around, 0. 9. So I’m not going, like I say, lower than that 0. 8. But it also depends on how I’m feeling and what’s been happening. If you’ve got any questions about this, I’d love to know.

Check out the show notes page if you want to see the little image that I’m talking about. And I’ll also try to put something up on my Instagram at some point. If you want to know anything else about monitoring your training load, planning your training load, if you’ve got any questions, just let me know and I can do a future episode.

Thanks so much for listening to today’s episode. I hope you enjoyed it. Just a reminder that you can find further [00:19:00] podcast episodes at http://www.siobhan-milner.com/podcast. And this is where you can also find different ways of working with me if you head to http://www.siobhan-milner.com. Enjoy.